First, I wish to give my traditional warning which must be given at this point in the year - and it is a warning which reminds us of that marvellous contraption called the Calendar, that so very Roman a thing - a scheme of feasts and fasts, but also a scheme of anticipation. Those big husky Romans, who so often seem to be the adults in the ancient world, were very much like little children when it came to their calendars. That is because unlike ours, their calendars were count-downs, not count-ups... but I have no time to lecture on that. My point of bringing up the old Roman calendar scheme is to remind you - that is, to give my traditional warning - about the approach of that most glorious day, the Kalends of July. You can keep your Ides of March, with its murder in the Forum. Give me the Kalends of July, with its mysterious depths...

You do not recall the allusion? Alas for you!

There are many great messages which have appeared in history - and in fiction, and I should list them here but I will unduly lengthen this essay. One of the greatest of these, one which epitomises some of my points from last week about problem solving, is the famous parchment, just 3 inches by 5, found within the Heims-Kringla of Snorre Tarleson, and scrawled with incomprehensible runes. After much difficulties, the message was found to read as follows:

In Sneffels Yoculis craterem kem delebat umbra Scartaris Julii intra calendas descende, audas viator, et terrestre centrum attinges.Which dog Latin being translated gives the following, one of the great secret messages of all literature:

Kod feci.

Arne Saknussem.

Descend into the crater of Yocul of Sneffels which the shadow of Scartaris caresses, before the Kalends of July, audacious traveler, and you will reach the center of the earth.Yes - next Thursday is the Kalends of July - so if you are going to try to get to Sneffels-jokull to follow Arne Sakneussemm - yes, it is REALLY there, check a map - you had better get over to Iceland real soon. I am not sure if the eruption of that other jokull (which Verne tells us is Icelandic for "glacier") will give us any grief, but it should be quite an adventure in any case.

I did it.

Arne Saknussemm

You don't know what I am talking about? Hurry to the library and read Journey to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne.

Now, of course you wonder - what did Chesterton have to say about such fantasies? You know as well as I do that he loved mysteries, so much so that he wrote them. You know as well as I do that he often expressed his thanks for the work of Arthur Conan Doyle - and even admiration for the writing of sci-fi guys like H. G. Wells: there's a very famous allusion to Wells' The Time Machine in GKC's The Everlasting Man, a lovely sed contra in the Scholastic form against Evolution and all its pomps.... but what about Verne? Well, there is not a lot but there is a little, and what there is, is delightful:

It would be grand (as in Jules Verne) to fire a cannonball at the moon; but would it not be grander to build a railway to the moon?And there is this, somewhat more intricate, and I will give you the entire paragraph for your delight:

[GKC "The Wings of Stone" in Alarms and Discursions]

I have just been entertaining myself with the last sensational story by the author of The Yellow Room, which was probably the best detective tale of our time, except Mr. Bentley's admirable novel, Trent's Last Case. The name of the author of The Yellow Room is Gaston Leroux; I have sometimes wondered whether it is the alternative nom de plume of the writer called Maurice Leblanc who gives us the stories about Arsene Lupin, the gentleman burglar. There would be something very symmetrical in the inversion by which the red gentleman always writes about a detective, and the white gentleman always writes about a criminal. But I have no serious reason to suppose the red and white combination to be anything but a coincidence; and the tales are of two rather different types. Those of Gaston the Red are more strictly of the type of the mystery story, in the sense of resolving a single and central mystery. Those of Maurice the White are more properly adventure stories, in the sense of resolving a rapid succession of immediate difficulties. This is inherent in the position of the hero; the detective is always outside the event, while the criminal is inside the event. Some would express it by saying that the policeman is always outside the house when the burglar is inside the house. But there is one very French quality which both these French writers share, even when their writing is very far from their best. It is a spirit of definition which is itself not easy to define. To say it is scientific will only suggest that it is slow. It is much truer to say it is military; that is, it is something that has to be both scientific and swift. It can be seen in much greater Frenchmen, as compared with men still greater who were not Frenchmen. Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, for instance, both wrote fairy-tales of science; Mr. Wells has much the larger mind and interest in life; but he often lacks one power which Jules Verne possesses supremely - the power of going to the point. Verne is very French in his rigid relevancy; Wells is very English in his rich irrelevance. He is there as English as Dickens, the best passages in whose stories are the stoppages, and even stopgaps. In a truly French tale there are no stoppages; every word, however dull, is deliberate, or directed towards the end.It is this sort of thing which I wish to inspire - no, not that my writing is like that - but I mean to urge you to attempt to treat each word, however dull, as being deliberate and directed to the end.

[GKC "The Domesticity of Detectives" in The Uses of Diversity

That is why I want you to consider that word "middle" which I put in the title - a word which alluded to "Center" - but which I chose for other - what some call "pedagogical" - reasons.

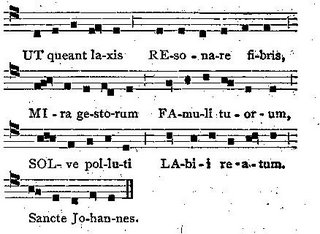

The middle often is the center. And often the center is akin to the ends, or at least in harmony with them. But sometimes the center (or middle) is very much at odds with the ends. Since today is the feast of St. John the Baptist, you ought to go about your business singing the famous Do-re-me song from "The Sound of Music" - or, preferably, the far more appropriate song called "Ut queant laxis":

[from Elson's Music Dictionary, 21. For more see here.)

Ut queant laxisThat is,

resonare fibris

mira gestorum

famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti

labii reatum,

Sancte Joannes.

This hymn was written by Paul the Deacon (720-799) and was chosen by Guido of Arezzo (990-1050) for the syllabic naming of the notes of the scale (given in bold).

That thy servants may be able to sing thydeeds of wonder with pleasant voices, remove, O holy John, the guilt of our sin-polluted lips.

[Matthew Britt, OSB, The Hymns of the breviary and Missal256-7]

Now, what is the middle between ut (the old name for "do") and Gamma (which also indicates the same note, middle C) ? It lies halfway between "fa" and "sol" - what the chromatic crowd call "F-sharp". This note, you may know, makes a dissonance with C (the augmented fourth), and you get the scary diminshed seventh (C-D#-F#-A) if you put two of them together... but let us proceed on our journey.

You may get a certain feeling of latent humor here - and you should. There's a schoolboy delight in realizing the foundation-keys of music arise in an ancient hymn to St. John the Baptist, and there's more where that came from. Chesterton uses a schoolboy error to warn us of the paradoxical dangers of the "middle":

All thinking people for thousands of years have agreed that, when all is said and done, there is such a thing as a golden mean, though perhaps the particular phrase is not very satisfactory. The true ideal is, rather, equilibrium, or, in other words, uprightness. There is something rather mean about the word "mean"; yet it is by no means easy to suggest a substitute devoid of such idle associations. No one can well be expected to talk idealistically about his "middle"; "balance" is associated with arithmetic and finance; while "medium" is associated with Spiritualism and with some sorts of gum. The schoolboy made a good shot at it when he translated "medio tutissimus ibis" as "the ibis is always safest in the middle." But under whatever form we take it, that ibis of the higher moderation, a chivalric and passionate moderation, must always be the crest of Christendom and of all sane civilisation. Unless that sagacious bird is allowed to be in the middle, there will be no place for the pelican of charity, the owl of wisdom, or the dove of peace.The Latin "medio tutissimus ibis" means "You will go more safely in the middle" and I am told is from Ovid's Metamorphoses. Here is some fodder for those who hunt for Chestertonian error. Does GKC urge us to stay in the middle, or to stay at the edge? Doesn't he tell us how Christianity had "a healthy hatred of pink"? [Orth CW1:302] Obviously we are not done with our journey to the middle.

[GKC Jan 20 1912 CW29:226]

Indeed. This is why I moaned last week about "problem-solving skills". Here is the same thing. When I first contemplated today's essay, I wanted to give some sort of brief introduction to automata theory - not to scare you, but to attract you. Instead, when I realized it was nearing the Kalends of July, and saw the mystic union of thought centering on the "center", I saw an even larger treasure to point towards. And yet, I find I am half-way to my desire!

For the real mystery of the middle is in grammar, which is of a deeper stratum than the mathematics of "middle" which we can simply express as (a+b)/2, and grammar is of the same order of thought as automata. In fact, for finite purposes, the two are one - a machine or automaton (the singular of "automata") is shown to be IDENTICAL to its grammar, and vice versa... but now I am like a lit'ry scholar boasting of why the Soothsayer bids Caesar "beware the Ides of March" - and why it wasn't just a copyist's error for "the Ideas of March" - or for the "Nones of April"... so let us defer that. Instead, I must tell you a very brief story, which may help.

Once I happened to meet a certain person who had taken some sort of introductory class which mentioned "computers" or something like that. Perhaps he felt somewhat uneasy in meeting me, an experienced computing professional, though I was then not yet a Doctor of computer science. But he wanted to show that he had truly learned something in that class, and indeed he was very excited about having taken it. So he asked me, "How many computer languages do you know?"

And I responded, "Oh, I'm pretty good at three or four. Maybe five."

To which he answered, "Well, I know over twenty."

And then he proceeded to list them.

You see, he meant he knew the NAMES of those languages - whereas I meant their USE. I could read them and write in them. He knew their names, and nothing more besides.

Now, when it comes to human languages, as soon as one begins to study them from within, one obtains a universal key to others - the key which is called GRAMMAR. (This, of course, is one of the primordial "problem-solving skills" - and hence it is hated by the moderns who find it loathsome instead of thrilling...) As soon as you know enough to grasp the sense of something like "word" or "sentence" or "verb" you have the master key to other things - yes, even to computing... but we must not go there today.

It is that hilarious word "verb" to which I must call your attention. No, not the ibis of safety, but rather the puzzle set up by the bratty little kid called "Calvin" (who played with a stuffed tiger called "Hobbes"). One of the more interesting strips went something like this:

Of course I felt a bit sad for Calvin, since poor English is so periphrastic - even in the best case, there's only five possible forms for a verb: eat/eats/eating/ate/eaten. And some other languages like Vietnamese have only one. But imagine if he had been speaking in Latin! Wow. Or even better - in Greek.

Calvin: I like to verb words.

Hobbes: What?

Calvin: I take a noun and put verb endings on it.

Hobbes: (looks confused)

Calvin: Verbing weirds language.

Hobbes: Eventually we can make language an impediment to communication.

[quoted from memory]

Now, here, I warn you. I admit to knowing ABOUT Greek - a very little ABOUT Greek. I do not pretend to KNOW Greek. You may recall what Chesterton says about this:

I myself have little Latin and less Greek. But I know enough Greek to know the meaning of the second syllable of "enthusiasm," and I know it to be the key to this and every other discussion.The second syllable, in case you did not know, means "God". I also have little Latin and less Greek, but I have learned some interesting things about these languages, and one of the most interesting is about the Greek verb. Greek seems, in almost every way, to be a far more powerful and delicate tool than English. It always seems to have something extra, something which we don't have in English, and would not even think about having. It was startling enough when I found out their nouns had an additional number. (That's the grammar word, not the math word!) You know, we can have one cat or several cats, one mouse or seveal mice - we have singular and plural.

[GKC The Thing CW3:139]

The Greek noun has something called the DUAL. (I am told English used to have it also, it shows up in some odd ways, when things regularly come in pairs, and why there's a mess in the uses of "between" and "among". Ahem.) What a handy idea! Greeks can have cat-2, (I don't know the real ending, so I write it this way). Having cat-2 is twice having one cat, and fewer than having several cats. Feel free to substitute the animal of your choice, if you prefer hippogriffs or dragons, use them: "A man cannot deserve adventures; he cannot earn dragons and hippogriffs." [GKC Heretics CW1:72]

Now, if that wasn't enough, to make extra endings for your nouns and pronouns (and adjectives and articles) to indicate one, or two, or many - the verbs are even more elaborate!

Of course verbs have to have the dual number. That proves handy for a husband-and-wife to speak with the dual voice - what a grand homage this makes to the sacrament of matrimony. (Which reminds me: let us not forget the anniversary of Gilbert and Frances is coming up next week...)

Greek also has multiple moods - not just indicative and subjunctive - who even knows what subjunctive is in English these days? (If I were a teacher... ahem.) And there are extra tenses, which someone like Marty McFly might have found useful when he went "back to the future"... I'm still not sure when "Aorist" fits in, but then I've never been sure about perfect and imperfect either. (If I could just get that flux capacitor to work, hmm.... where am I going to get 1.21 gigawatts?)

But here's the really stunning one, the one you've been waiting for.

The English verb has two voices: active and passive. Active is when I act: "I wash the car." Passive is when I am acted upon: "As a baby I was washed by my mother."

But - the Greek verb has three voices. Guess what the third one is called.

Yes. It's called the Middle Voice. It means I act upon myself: "I wash myself every morning."

Now, that's another handy problem solving skill - and you didn't even have to go to Iceland.

The Middle Voice is even greater than you say. It is often introduced as a reflexive ("I act upon myself"), but it often is more nuanced than that. You can read more about it in this paper: http://www.artsci.wustl.edu/~cwconrad/docs/UndAncGrkVc.pdf

ReplyDelete